The Carracci Drawings: The Making of the Farnese Gallery at louvre, paris

Trois Crayons Magazine, January 2026

Reviewed by Daniel Lowe, contributing editor

Vault of the Farnese Gallery. Palazzo Farnese, Rome. Per gentile concessione del Ministero della cultura, Soprintendenza Speciale Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Roma.

Curating a major exhibition dedicated to the Carracci — the Bolognese brothers Annibale and Agostino, and their cousin Ludovico — can be a hazardous affair. Centuries of turbulent critical reception, a dense and often discordant bibliography, and (as much as it pains the writer to say it) occasional public indifference has made it incredibly difficult to do justice to the work of the Bolognese artists in a museum setting. It is precisely for this reason that The Carracci Drawings: The Making of the Farnese Gallery (Dessins des Carrache. La fabrique de la galerie Farnèse) is a particularly daunting and ambitious prospect.

Curated by Victor Hundsbuckler, the Parisian exhibition largely focuses on the preparation of the frescoes of the Galleria in Palazzo Farnese in Rome, painted by Annibale and Agostino Carracci for Cardinal Odoardo Farnese at the turn of the seventeenth century. The Galleria frescoes depict various amorous encounters of the Roman Gods, organised using a revolutionary system of illusionistic painted frames known as quadri riportati. The artists were aided in this feat through the peerless advice of Odoardo’s librarian Fulvio Orsini, and the manual aid of a handful of assistants. Through the brothers’ breathtaking drawings, the exhibition masterfully illustrates the painstaking preparation necessary to decorate the twenty-metre-long gallery, alongside the dramatic consequences the project had on Annibale’s mental state and relationship to his brother.

The exhibition is arranged in two separate rooms in the Mezzanine Napoléon. Its unusual chronological approach follows a roughly backwards order, discussing the Farnese frescoes in four sections: the reception of the decorations, the vault and walls of the Galleria, the Camerino, and a series of thematic groups featuring drawings by the Carracci made in Bologna before their Roman period.

The first of these sections contains portions of a to-scale drawn copy of the Galleria’s ceiling, executed in 1667 by François Bonnemer, Jean-Baptiste Corneille, Pierre Mosnier, Bénigne Sarrazin, and Louis René Vouet. Commissioned by King Louis XIV, these copies served as a guide for a second team of painters to replicate the Farnese Vault in the Galerie des Ambassadeurs in the Parisian Palace des Tuileries. Placed at the beginning of the exhibition, they marvellously illustrate both the sheer scale of the Carracci’s undertaking, as well as the prestige and influence their frescoes had decades after their completion. This also gingerly avoids the much-dreaded ‘reception section’ at the end of many exhibitions, which can briskly curtail the visual ecstasy of the viewer.

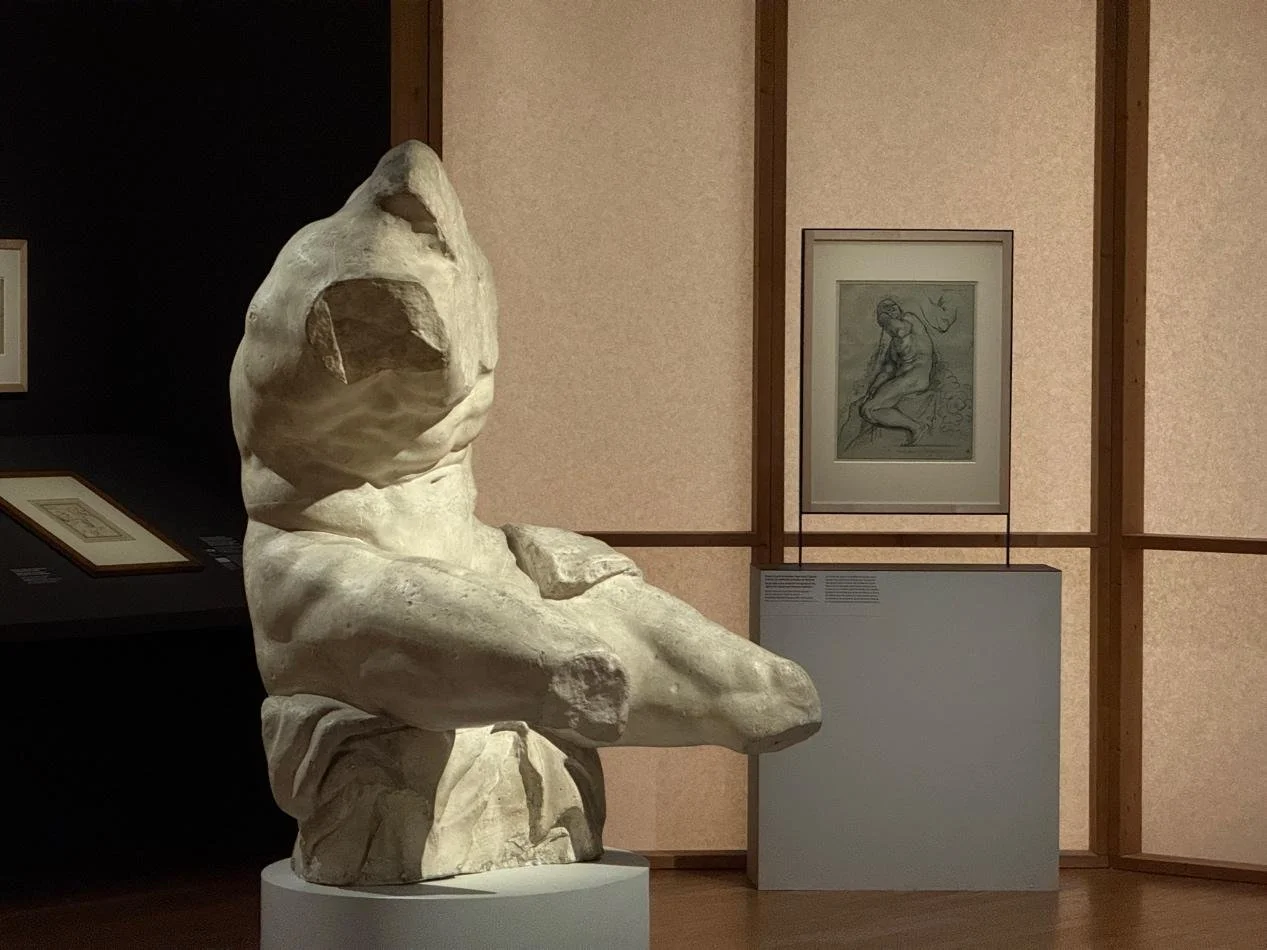

Dessins des Carracche, installation view.

The show continues with exquisite preparatory drawings for the Farnese Gallery, grouped by scene (e.g. Jupiter and Diana, Mercury and Paris) or by the elements that surround them (herms, ignudi, amorini). The sheer number of preparatory sheets on display, largely drawn from the Louvre’s own holdings and from exceptionally generous loans from the Royal Collection Trust, is a triumph. A clear highlight is the striking cartoon for the right-hand portion of the Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne, on loan from the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino.

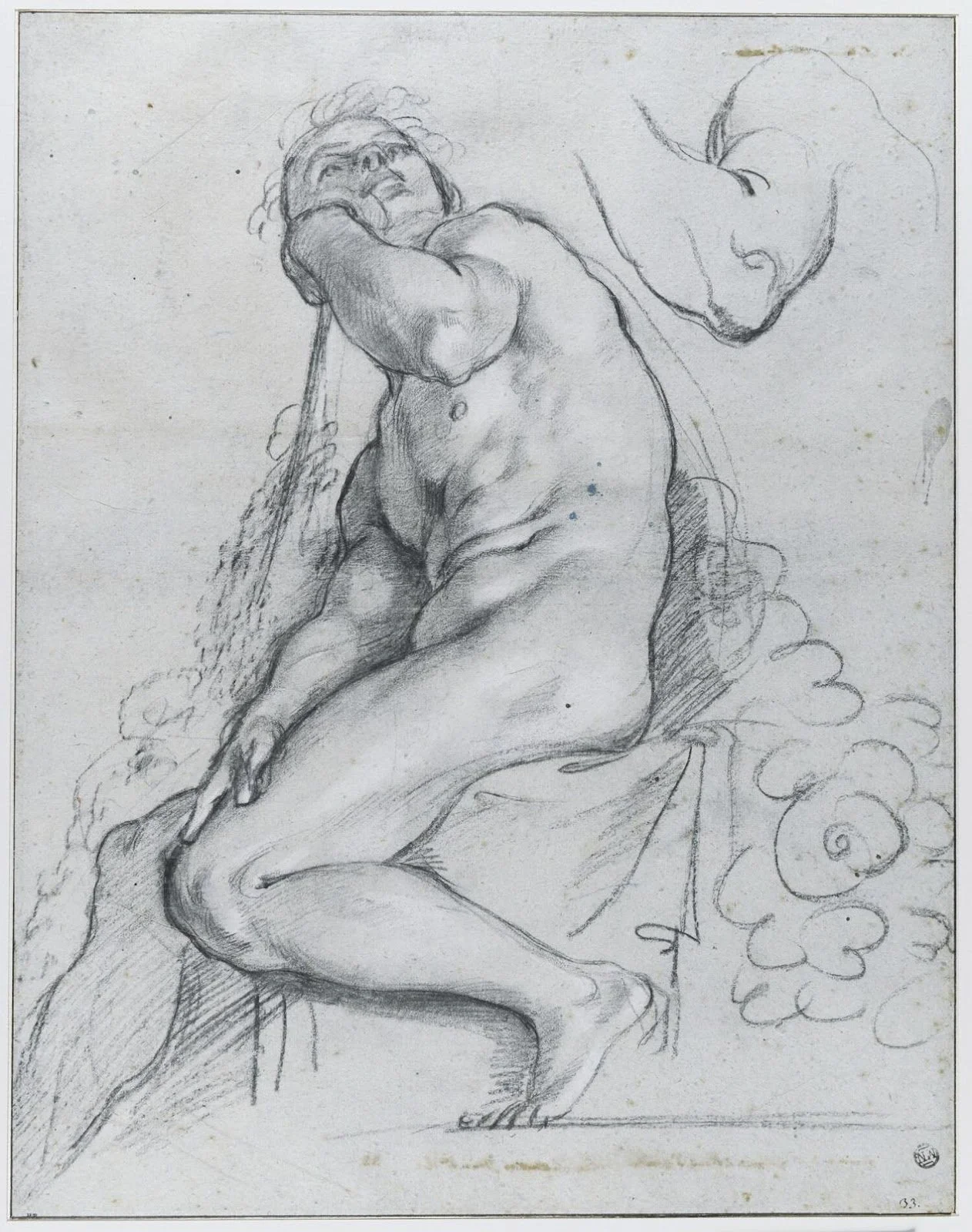

Annibale Carracci, Étude pour « l’ignudo » à droite du médaillon d’« Apollon et Marsyas ». Musée du Louvre, Paris, département des Arts graphiques © Musée du Louvre,dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Suzanne Nagy.

To assist viewers in connecting the preparatory drawings to the finished frescoes, the sheets are cleverly placed under a 70 percent-scale rendering of the Farnese vault by Margaret Gray, carefully adjusted to reduce distortion. Alternatively, visitors may also compare the frescoes with the drawings on display on a dedicated website, accessible via a series of QR codes. Overall, this section gently guides the spectator into prolonged, engaged close looking, and highlights the immense preparation and fatica required to execute such a large project.

Dessins des Carracche, installation view.

The second room begins with drawings for the walls of the Galleria together with several thematic sections which highlight sources of inspiration for the Carracci workshop. Drawings for Perseus Fighting Phineas — painted by Annibale and his assistants a few years after Agostino left Rome for Parma, where he would die in 1602 — are displayed near drawings made after the antique and earlier masters of the Roman Cinquecento. Exposure to the city’s wealth of ancient statuary, alongside paintings by the likes of Michelangelo and Raphael were transformative for the Carracci brothers. The artists blended these new Roman visual sources into their pictorial style, largely based on Bolognese and Venetian models. The show presents this wonderfully ‘pan-Italian’ style, traditionally branded with the pejorative term ‘eclectic’, as the fruit of the effervescent hunger and adaptability of the artists.

The exhibition continues its march back in time with the preparatory drawings for the Camerino, a private room near the Galleria. The painted decorations for this space, featuring images of princely virtue drawn from Classical mythology, have fared far worse than the Galleria over time, with elements being removed, damaged and retouched. As such, the presence of another photomontage by Gray, which aims to reconstruct the ceiling of the space as it would have originally looked, is a real boon here.

The chronology and attribution of the Camerino (and indeed, the Farnese Frescoes as a whole) is a highly contested matter. Some scholars, such as John Rupert Martin (1965), view them as a ‘test run’ for the much larger Galleria, painted by Annibale alone and completed before 1597. Others, such as Silvia Ginzburg (2015), think that the Camerino was executed when the Galleria’s frescoes were already underway (c. 1599), with heavy involvement from Agostino and Annibale’s assistant Innocenzo Tacconi. Whilst the catalogue is justifiably ambiguous about the dating of the frescoes, the reverse order of the show required that a date was chosen to ‘place’ them within the non-linear timeline. In the end, the earliest possible chronology of 1594 (the brothers’ initial arrival in Rome) was chosen, and Annibale assigned as the main author.

The exhibition continues with a small thematic section, which tackles the thorny question of the extent of Agostino’s involvement in the Galleria. Although the elder Carracci brother’s role in this feat has long been wrongly minimised, the show seeks to remedy this not by engaging in over-granular debates of re-attribution but by reframing the production of the Carracci as a team effort. Indeed, all object labels in the exhibition place attributions in the middle of the caption, prioritising the function of the drawing rather than its individual creator. This is in line with how the Carracci themselves would have viewed their production. Malvasia records Ludovico’s comment upon being asked to identify the authorship of different portions of the Palazzo Magnani frescoes in Bologna: ‘It’s by the Carracci; all of us made it’ [ella è de’ Carracci: l’abbiam fatta tutta noi]. Other sections highlighting the ‘singularities’ of the Carracci follow, including their wicked sense of humour, and their affection for so-called ‘gente bassa’ (i.e., the poor and disabled). This last section features Annibale’s exquisite red-chalk Hunchback from Chatsworth, a sheet of disarming pathos. The label for this drawing presents the heart-wrenching inscription ‘Non so se Dio m’aiuta’ [‘I don’t know if God helps me’] as being by Annibale’s own hand; this has been the subject of debate, with scholars such as Jaffé (1994) in favour, and some like Benati and De Grazia (both 1999) against. To the reviewer, the ‘decorative’ and pathos-inducing inscription seems more in line with the motives of a later collector than those of the decidedly un-saccharine Annibale. In any case neither possibility can be definitively excluded.

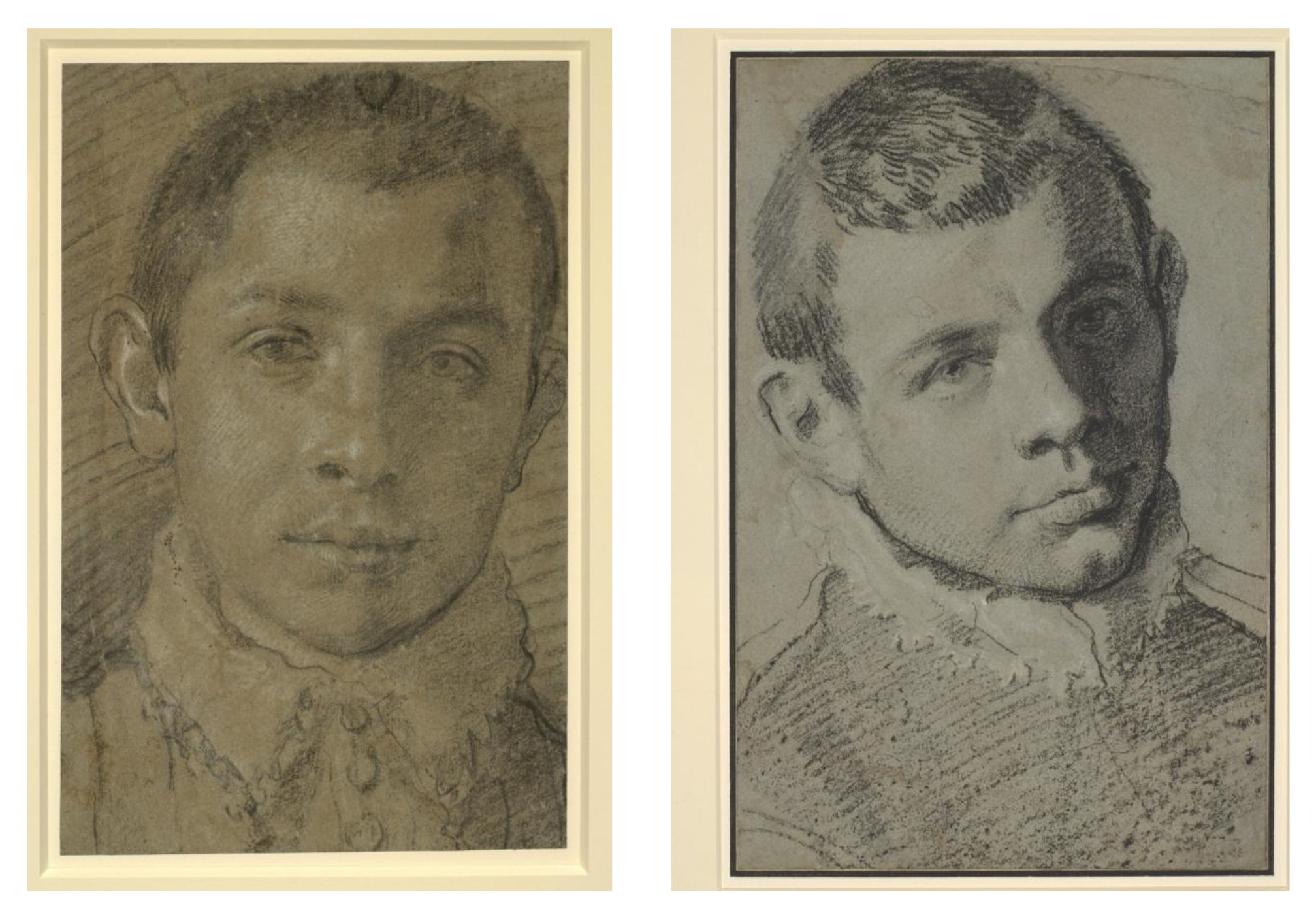

Left: Agostino Carracci. Autoportrait présumé. Lent by His Majesty The King from the Royal Collection © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust. Right: Annibale Carracci. Autoportrait présumé. Lent by His Majesty The King from the Royal Collection © Royal Collection Enterprises Limited 2025 | Royal Collection Trust.

The final room highlights how the spirited unity of the Carracci would ultimately meet its undoing in the Farnese Gallery. Two presumed self-portraits on blue paper from the Royal Collection Trust, likely made before the Farnese campaign, depict the brothers as young, ambitious, and almost identical. After fighting about the project — reportedly due to the diligent-yet-callous Annibale’s rage toward the learned and somewhat sycophantic Agostino, who constantly brought people onto the scaffolding to view the frescoes — a void was left in Annibale’s psyche. Two ‘symbolic’ self-portraits, each depicting a lonely, melancholic figure within the Galleria, show the utter sfinimento and ‘mortal depression’ of the artist at the end of the demanding project, for which he would receive a measly five hundred scudi.

Adding to the ambition of the show is its catalogue. More than a simple register of the works on display, the publication includes all drawings made in preparation for the Galleria and Camerino, adding sixty-three sheets to John Rupert Martin’s inventory of 1965. The essays in the publication masterfully expand on the themes explored in both rooms. Of particular note is ‘Ambiguïtés. Dire et taire l’amour’ (pp. 211-228) which explores how the ancillary elements outside of the quadri riportati imbue the various Loves of the Gods with tantalising erotic ambiguity.

The publication’s prologue (pp. 23-26) perfectly resumes the philosophy of the entire show. Not only does the exhibition seek to re-tell the fascinating and turbulent history of one of the most important ceilings in Italian art, but it strives to get its visitors to engage in the careful, slow examination necessary to appreciate any Old Master drawing. Hundsbuckler’s incipit makes an impassioned and poetic case: whilst digital images are being harnessed for profit via sinister algorithms and advertisements, cultivating careful scrutiny of something beautiful, something real, for no other purpose than one’s unconditioned pleasure is an act of civic emancipation and resistance. Allow this reviewer to close, in concert with his sentiments, with an excerpt from Schiller’s Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen: ‘when we find in man the signs of a pure and disinterested esteem, we can infer […] that humanity has really begun in him.’

The Carracci Drawings: The Making of the Farnese Gallery continues at the Musée du Louvre until 2 February.