Demystifying Drawings #28

Tuesday, 6 January 2026. Newsletter 28.

Recent Advances in Watermark Research

Dr Robert Fucci of the University of Amsterdam in conversation with the editor

When confronted with a drawing whose date and region of production are unknown, one of the few material pieces of evidence is the paper’s watermark. A watermark is a translucent impression created by the wires attached to the papermaking mould. These marks can be revealed under transmitted light and can take a variety of forms, styles and sizes, from fabulous creatures, to coats of arms and geometrical figures. Accurate interpretation of these marks allows art historians to identify the manufacturer of the paper, as well as the geographic area where it was produced and the approximate date of manufacture, thus providing firmer contextual ground for further investigations into the drawing’s materials, iconography and attribution.

Dr Robert Fucci of the University of Amsterdam is part of a team at the RKD – Netherlands Institute of Art History that is currently working on a new systematic approach to watermark research in drawings from the school of Rembrandt. We sat down to learn more…

Watermark research has long formed part of the art historian’s technical toolkit, though it is not without its challenges. Could you outline this new scope of this project and how it seeks to advance the field of watermark studies?

In terms of analysis, we are making advances on two fronts. One is that we are using digital techniques to make sure the watermark matches are as precise as possible. Just using your eyes to compare watermarks is trickier than you might think, since the subtle differences can be difficult to detect. So, we have software that creates overlays in order to confirm an exact match. The second front has an even greater potential long-term impact, which is: we are creating digital libraries of watermarks. Once we have a watermark scanned, marked, and stored in the library, we can confirm a match very quickly, even with large datasets.

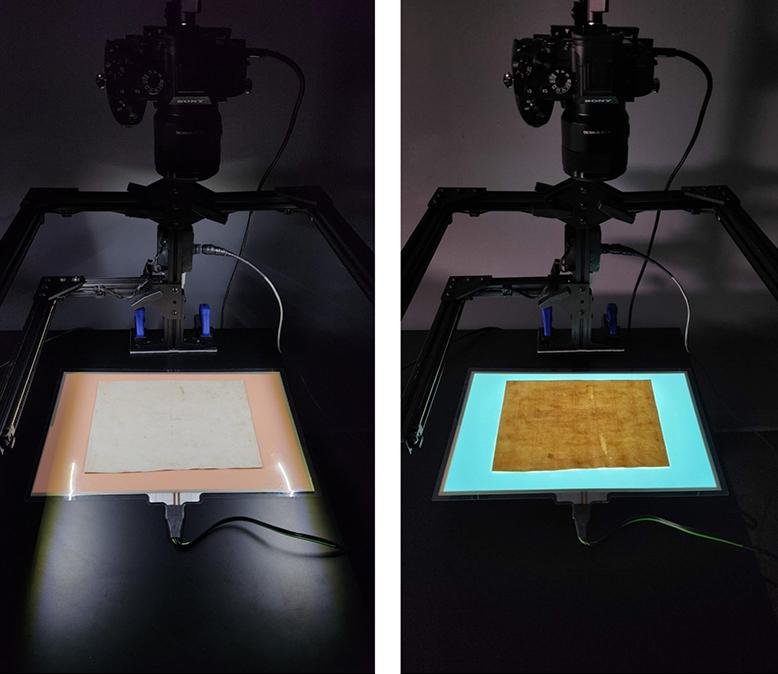

Your research utilises a new technology, the Watermark Imaging System (WImSy). How does this technology operate in practice, and in what ways has it transformed the process of watermark imaging and comparison?

The WImSy device is very exciting because, first of all, it is transportable. We can take it to visit collections that do not have a similar scanning device, whether because they do not have the means to invest in one, or (more often) they simply do not have enough drawings to justify the expense. This device photographs drawings using transmitted light to capture a series of images of the watermark, and then digitally removes the recto image (i.e. the drawing itself) in order to make the watermark clear enough for analysis.

The project is built on extensive interdisciplinary collaboration which brings together (computational) art historians, conservation scientists, and digital-signal-processing specialists across institutions in the Netherlands, the United States, and beyond. How have these partnerships broadened both the methodological reach and the interpretive possibilities of the project?

We simply would not have a project like this if it were not for innovative engineers such as Rick Johnson and Bill Sethares (who designed the software), and conservation scientists such as Paul Messier (who designed the WImSy device). Thankfully, they still need art historians like myself to target the watermarks and interpret the data, which makes for a highly fulfilling collaborative venture.

Drawings by Rembrandt and his circle are the focus of this project. Why this group of artists and how might this concentrated focus enrich (or complicate) our understanding of seventeenth-century studio practice around Rembrandt?

A focus on Rembrandt and his circle makes perfect sense for this pilot study, since, first of all, we needed to limit our scope in order to have conclusions that we could make within the twelve months that are carrying out this initial study. And what better artist than Rembrandt? I suppose if we knew of any drawings by Vermeer or Frans Hals, then we could have also studied those, but sadly there are none. What makes Rembrandt a particularly compelling subject, though, is that for a number of years he was at the head of one of the largest artist ateliers in Northern Europe, and certainly the largest in Amsterdam during his height. It gives us a chance to study this highly creative environment better.

The systematic documentation generated by this project promises to be a valuable resource for future researchers. When and where will these findings be made accessible to the public?

We are working on it. The watermark scans will soon be made available online through the RKD website. We have also offered workshops at the RKD to train researchers how to use the software to analyse watermarks themselves, and to build the digital library, and we hope to continue to offer more such workshops in the future.

The technology and methodology appear adaptable to a wider range of works on paper. Are there plans to expand the project’s scope or apply WImSy-based analysis to other periods or regions?

It is a question at this point of grant funding, staffing, and institutional commitment, but yes, this project certainly has tremendous expansion potential, and we hope to generate interest in that.

Finally, have any early results or unexpected discoveries emerged that you are able to share?

We will soon publish some of the art-historical results of the project, including data that shows shared paper use among the artists working in Rembrandt’s atelier, and even some data that suggests revisions to the dates of some of Rembrandt’s own drawings, dates that had previously been based upon traditional connoisseurship alone. One of the most interesting results is that earlier generations of connoisseurs appear to have been more accurate, on occasion, in their dating of certain drawings by Rembrandt than more recent generations who attempted to revise those previous assessments!