Reviews #8

Wednesday, 1 May 2024. Newsletter 8.

Bruegel to Rubens: Great Flemish Drawings (23 Mar – 23 Jun)

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Workshop of Tomasso di Andrea Vincidor (1493–1536), Fragment of a Tapestry Cartoon: Bust of a Woman in Profile, Christ Church, Oxford

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1526–69)The Temptation of St Anthony, c. 1556 Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

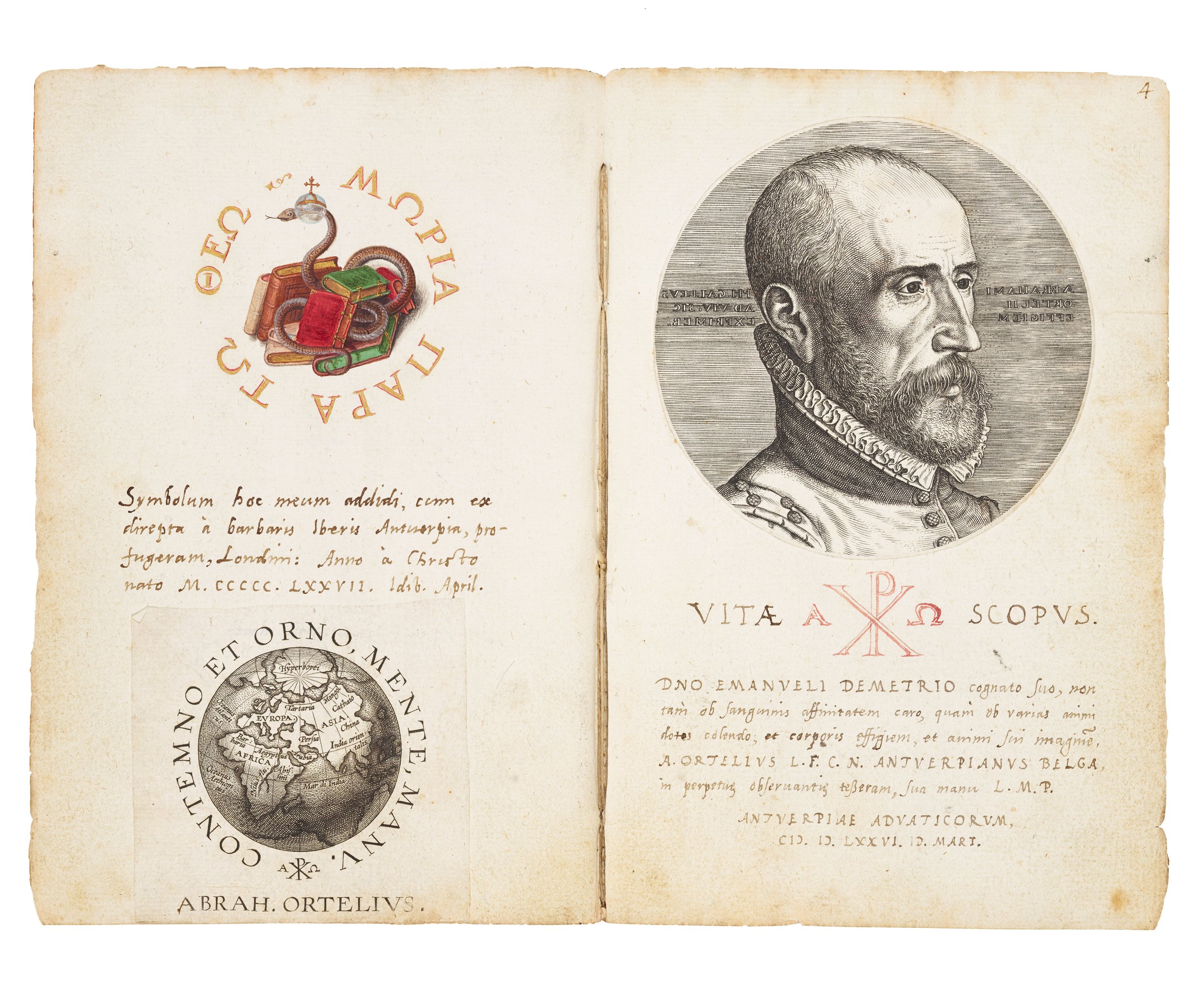

Album Amicorum of Emanuel van Meteren, 1576 & 1577, Friendship Contribution by Abraham Ortelius, folios 3v–4r, The Bodleian Libraries, Oxford

An Interview with An Van Camp, curator of the exhibition and Christopher Brown Assistant Keeper of Northern European Art, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the timespan covered by the exhibition, Flanders, historically located in the Southern Netherlands and today a region of Belgium, was Catholic and governed by the Habsburg rulers of Spain. Drawings such as Pieter Bruegel’s raucous ‘The Temptation of St Anthony’ quickly dispel any misconceptions of sober Catholic orthodoxy in the region’s artwork, however. The drawings on display here are not bound by the urban centres of religion in which many of them were produced. They reveal the breadth of drawing’s potential functions, as well as representing both intimate local observations and a newfound worldliness, as the region opened up to trade and voyage, whilst the artists themselves looked south to Italy.

Could you outline the scope of the exhibition, the artists and artworks involved, and, perhaps most importantly, explain why readers should certainly make the trip to Oxford.

Bruegel to Rubens features almost 120 drawings, which were created by artists either working in or born in the Southern Netherlands during the 16th and 17th centuries. The exhibitions stems from a partnership with the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, who staged a reduced version of the show between November 2023 and February 2024. For the second venue at the Ashmolean Museum, we have chosen around 50 of the most exquisite drawings from Antwerp public and private collections, supplemented with Oxford’s finest sheets. The majority was naturally selected from the Ashmolean Museum, with additional loans from Christ Church college and the Bodleian Libraries. Over a quarter of the drawings are by Antwerp’s best-known Baroque son, Peter Paul Rubens, expanded with works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hans Bol, Joris Hoefnagel, Jan van der Straet (Stradanus or Stradano), Maerten de Vos, Anthony van Dyck, Jacques Jordaens, Abraham van Diepenbeeck, Jan Boeckhorst etc. The exhibition focuses on how these drawings were used in artistic practice at the time, with the three galleries divided in the three main functions of South Netherlandish drawings: sketches of the world around them, including copies of other artworks and studies from life and nature; designs for other artworks, such as paintings, prints, stained glass, metalwork, tapestries, sculpture, temporary decorations and architecture; and finally, independent drawings made in their own right. Many of the Antwerp drawings are listed on the Topstukkenlijst (designated “Masterpieces” by the Flemish Government) and, because of their fragility and sensitivity to light, are not allowed to be shown again for the next ten years or so. In addition to Oxford drawings, many of which have never been displayed or published before, Bruegel to Rubens is truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see so many superb South Netherlandish drawings together. Bruegel to Rubens is still on until 23 June.

What message do you hope to convey through your curation of the exhibition?

I wanted to curate an exhibition in which the drawings were presented to the visitors in the most accessible way. The general public often still considers “old master” drawings as only understood by a select number of connoisseurs and specialists. However, by revealing how and why the artworks were made, we decided not to focus on their iconography or attribution, but rather highlight their function and related drawing techniques. These 16th- and 17th-century sheets were used as training and workshop materials, in addition to having been created as standalone artworks. The first room, dedicated to Sketches and Copies, introduces the various materials and techniques on the introductory wall and in a showcase. We even recreated Rubens’s drawing desk in a large display case through a variety of Ashmolean objects (Roman coins and intaglios, antique sculptures, Renaissance bronzes and plaquettes, Antwerp printed books), which feature in Rubens’s drawings (which are represented through facsimiles), in addition to drawing materials such as a quill, an inkpot and sheets of paper. It has been highly satisfying to see not only the visitors’ reactions but also to hear from other drawings specialists how effectively this one display brings the subject to life. The exhibition has succeeded in making visitors understand that these precious and fragile artworks were not always regarded as high-value artworks in collections, now professionally mounted and framed, but instead that they served a variety of practical functions at their time of creation.

Does the exhibition offer any new interpretations of the objects displayed, and were there any surprising discoveries made during the research process?

Because of the Antwerp-Oxford partnership, Bruegel to Rubens has managed to unite a unique collection of drawings which have never been shown together before. Over 30 drawings are in fact on display for the very first time and have only been recently (re)discovered and published. It was also possible to juxtapose related works kept in the various museum collections, such as for instance two designs by Jan Boeckhorst for the same tapestry and a Rubens title-page design shown with the copperplate made after it and the final printed version. We also united for the very first time six life-size tapestry cartoon fragments for the Vatican tapestry showing The Presentation in the Temple. In preparation of the exhibition, the Ashmolean was able to acquire an early impression of Pieter Bruegel’s The Temptation of St Anthony, of which we own the drawn design and is one of the best-loved drawings in our collection.

The accompanying catalogue is intended to be consulted beyond the exhibition and to act as a manual to South Netherlandish drawings. The three main essays deal with the three major functions of drawings, as discussed above, and include one feature each focusing on sub-themes running through the exhibition: the internationality of the artists, their professional collaborations, but also their personal friendships and networks. Two introductory essays explain what a drawing is on a material-technical but also conceptual level, as well as provide a historical/geographical/cultural context of the Southern Netherlands.

As Vincent van Gogh wrote, drawing “is the root of everything”. Could you expand upon the relationship between drawings and the artworks produced in other media which are highlighted throughout the exhibition.

For centuries drawing has been described as the “Father of all the Arts” or the “Gateway to all the Arts” (Vasari and Karel van Mander). In Bruegel to Rubens this becomes all the more apparent. In the first gallery, Copying and Sketching, the different sub-sections reveal how artists started their artistic training by making copies and sketches of everything around them. It was less daunting to start copying from existing prints, such as Rubens’s album with copies after Hans Holbein II’s Dance of Death woodcuts. Budding artists then moved onto copying drawings, paintings, and eventually, three-dimensional objects such as sculptures. Once proficient, draughtspeople would venture beyond the study and make studies from nature, often en plein air, to finally attempt to make studies from life, such as portraits, tronies, but even snapshots of their pet animals and even an earthworm. But not only pupils would practice drawing and many artists continued to draw in order to create similar studies, but also designs for other artworks and independent sheets. No matter which specialism the artist would end up, whether painting, printmaking, sculpture, architecture, decorative arts (metalwork, stained glass, and tapestries), drawings would usually lay at the base of any artwork created. This is illustrated in the second gallery devoted to design drawings, featuring both compositional studies, as well as detail studies, life-size designs or smaller compositions than the final artwork.

The Netherlands was in a state of flux during this period. How are the external influences of war, travel, trade, and colonial expansion reflected - or ignored - in some of these drawings?

Many of the drawings in the exhibition reveal the political and religious context against which they were created. The Southern Netherlands were not an independent region, but were under Spanish rule through local governors. Catholicism was imposed and this caused numerous rebellions, followed by persecutions of other religions. A set of designs for metal plaquettes by Maerten de Vos illustrate several historical events of the Liberation of Antwerp in 1577 from the Catholic Spanish, however this was very short-lived. Two drawings are designs for temporary decorations (now lost but documented through these sheets) erected during Joyous Entries, when the Spanish governors established their rule. Some of the artists featured in the exhibition were Protestant and were either exiled or fled to more tolerant regions such as up North to the Dutch Republic or East to the Holy Roman Empire. Some of the most stunning cabinet miniatures in the exhibition were possibly made for the courts in Munich and Prague, such as for instance Joris Hoefnagel’s Arrangement of Flowers. Most Netherlandish artists travelled within Europe as part of their training, with Italy being the top destination in order to learn from antiquity and Italian painters. Almost ten percent of the drawings on display were made in Italy, featuring copies of antique sculptures and gems, as well as Roman ruins, but also works by artist who permanently settled in Italy but kept proudly referring to themselves in their signatures as “Flemish”, such as Jan van der Straet (Giovanni Stradano) and Denys Calvaert (Dionisio Fiammingo).

Do you have a favourite drawing in the exhibition, or a favourite story that has come out of it?

When I was preparing the object selection for the exhibition, I came across a relatively unknown artwork, now kept at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford. It is the friendship book or album amicorum belonging to the Antwerp historian Emanuel van Meteren. These alba have for many centuries been a widely popular socio-cultural phenomenon in large parts of Europe, including the Southern Netherlands. Surprisingly, British audiences are not familiar with the concept or holding a friendship album and requesting friends, family members, teachers, and colleagues to make contributions in them. These are usually kept for life and treasured as a reminder for long-lost or everlasting friendships. Emanuel van Meteren wrote a history of the Netherlands and was moreover a nephew of the foremost Antwerp cartographer Abraham Ortelius. His album is filled with numerous contributions by his peers, including his uncle’s but also masterpieces by contemporary artists and humanists such as Joris Hoefnagel, Lucas d’Heere, Philips Galle, Hubert Goltzius, Justus Lipsius etc. The pages opened in the exhibition contain two contributions Abraham Ortelius: one created in 1576 with a portrait print and his motto, followed up by a second contributed added a year later after the Spanish Inquisition had confiscated Van Meteren’s album in order to identify his Protestant network. Ortelius skilfully, but daringly, drew an allegory of the Spanish king Philip II as a serpent coiled around a pile of books.