August 2025

friday, august 1

Trois Crayons celebrates the art of drawing from the 15th to the 21st century. From in-person exhibitions and collaborative events to our monthly newsletter and social media activity, we connect the global drawings community.

Coming Up

Greetings from Trois Crayons HQ where the team is taking stock after Tracing Time and preparing for a summer break. We wish you all, dear readers, an equally happy and restful August.

This month’s newsletter is replete with a holiday’s worth of drawings news, upcoming events and exhibition listings. The ‘Drawing of the Month’ is selected by Gode Krämer from the newly-opened exhibition at the Kunstsammlungen & Museen Augsburg, and for the ‘Demystifying Drawings’ feature, the contemporary artist Nicholas C Williams reflects on Timeless Materials, a panel discussion held at Tracing Time in which three artists considered their relationship with drawings, materials and the past. For this month’s review, Nigel Ip visits Leighton House to explore Victorian Treasures from Cecil French and Scott Thomas Buckle. All this is followed by the customary selection of literary, video and audio highlights.

For next month’s edition, please direct any recommendations, news stories, feedback or event listings to tom@troiscrayons.art.

TROIS CRAYONS MUSEUM FORUM

Museum Partner Highlight: Princeton University Art Museum

As part of a new monthly feature spotlighting works shared for discussion on the Trois Crayons Museum Forum, we are pleased to highlight a recent submission from the Princeton University Art Museum: Girl Drawing a Profile, and Four Heads of Youths by an unknown Italian artist.

To participate in this and other ongoing discussions, please click here. To register as a Museum Partner, please email info@troiscrayonsforum.org.

Image courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum

Curator’s comments: When this drawing was accessioned through the bequest of Dan Fellows Platt, it held an attribution to Baccio Bandinelli. In 1968, Felton Gibbons suggested the drawing be attributed to the Neapolitan artist Giovanni Battista Caracciolo (Il Battistello), citing stylistic similarities with sheets by the artist included in the Uffizi exhibition Cento disegni napolitani in 1967. While the drawing of the écorché leg on the verso is not copied from any early anatomical print illustrations, according to Monique Kornell, it may be comparable to the kind of drawings created in the Bolognese academies of the Carracci or Guercino. The sheet is particularly notable because it depicts a woman drawing. The depiction of her hands holding the quill pen can be likened to a print of hands writing in the Scuola perfetta, a drawing manual by Luca Ciamberlano with engravings after designs by Agostino Carracci. We are seeking additional comparatives and further attributional suggestions.

NEWS

In Lecture and Event News

7 August – Lecture, Gustave Caillebotte: The Artist as Collector, Art Institute of Chicago (Chicago): Talk by curatorial assistant Megan True at 6pm, exploring Caillebotte’s collection and its legacy.

11–12 September – Conference, FOCUS 1600, Schloss Johannisburg ( Aschaffenburg): The third Aschaffenburg symposium on the art and culture of Mannerism is entitled: Unlimited possibilities? Drawing in Mannerism. Admission is free. For the evening reception, please register at info@museen-aschaffenburg.de.

6 November – Evening Reception: Past Matters: Drawn to Discovery at the Antiquaries, Society of Antiquaries of London (London): An evening reception with Abbott & Holder at the Antiquaries for a curated selection of highlights from the Society’s remarkable collection of over 45,000 17th- to 20th-century prints and drawings. Tickets are £30 and all proceeds go towards supporting development plans for Burlington House.

4–5 December – Conference, Turner 250, Tate Britain (London). Timed to coincide with the Turner and Constable exhibition at Tate Britain and to help bring celebrations of Turner’s 250th anniversary year to a close, this conference will take Turner’s art and life as a starting point for exploring what it means to research Turner and to curate his work today.

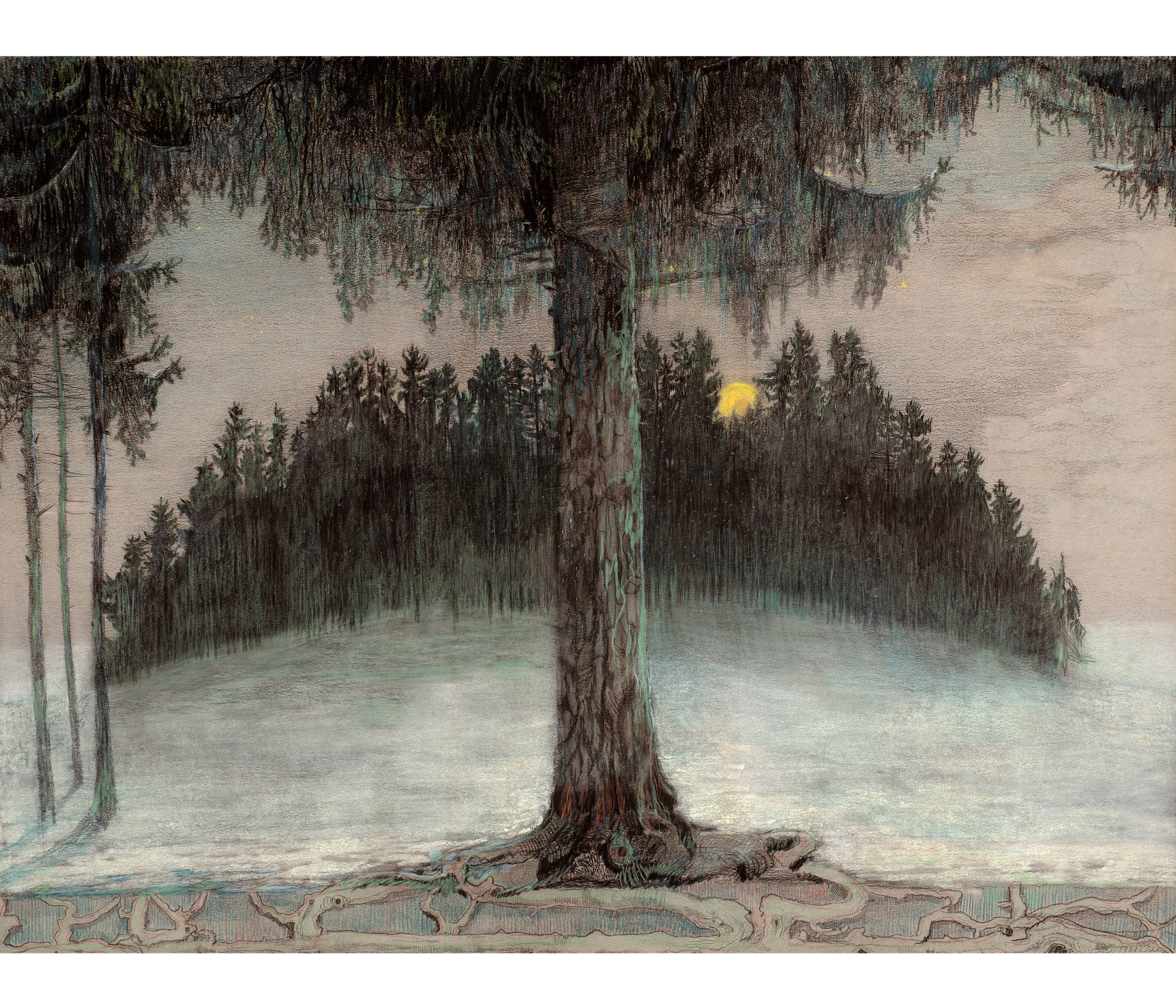

Emilie Mediz-Pelikan (1861–1908), Larch Forest by Full Moon, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Regenstein Endowment Fund, inv. no.: 2025.214

In Literary and Academic News

Job opportunity – Paper Conservator, Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg (Coburg): Permanent full-time position starting 1 November 2025.

Job opportunity – Curatorial Traineeship, Royal Academy of Arts (London): Two positions available in the Genesis Future Curator Programme, a two-year traineeship focused on exhibitions and collections.

Job opportunity – Editorial Assistant/Associate, Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History (Rome): Part-time post with the Lise Meitner Group “Decay, Loss, and Conservation in Art History,” led by Dr. Francesca Borgo; start date 15 September 2025; application deadline: 15 August.

Call for papers – ART, INC., Courtauld Institute of Art (London): Submission deadline: Friday 5 September 2025; symposium to be held 5 December 2025.

Call for applications – Workshop on the Research and Curatorship of Drawings Part II (Weimar): Hosted by Klassik Stiftung Weimar and supported by the Getty Foundation’s Paper Project; application deadline: 6 August; workshop dates: 20–21 November 2025.

Seminar – The Craft of the Connoisseur: The Challenge of Portraiture, Fondazione Federico Zeri (Bologna): For recent graduates; seminar dates: 18–20 September; cost: €200; applications due by 4 September via fondazionezeri.iscrizioni@unibo.it.

In Acquisition News

Pierre Fontaine (1762–1853) and/or Charles Percier (1764–1838), Vue animée de la Salle des Empereurs romains et du Grand Vestibule au Musée royal: Acquired by the Musée du Louvre from Galerie Terrades (via Facebook).

Jean-Jacques de Boissieu (1736–1810), King David Playing the Harp: Acquired by the Fondation Custodia from Sotheby’s (via Facebook).

Emilie Mediz-Pelikan (1861–1908), Larch Forest by Full Moon: Acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago from Agnews.

Giovanni Battista Bertani (1516–1576), The Virgin Annunciate (Design for Organ Shutter): Acquired by the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), Studies for a Roman Matron Seated on an Ancient Throne, A Woman Carrying a Drum, and A Scene of Mourning Women (The Death of Camilla?): Recently acquired by the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Paulus Pontius (1603–1658), Adoration of the Shepherds: Acquired by MUŻA, Malta.

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Étude préparatoire pour 'La Grèce sur les ruines de Missolonghi': Donated to the musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux by the Société des Amis du musée; on view with the final painting from 3 November.

John Everett Millais (1829–1896), Archive including over 150 works on paper, 19 oil paintings, correspondence, studio tools, and family heirlooms: Long-term loan to the Perth Art Gallery from Sir Geoffroy Millais, great-grandson of Millais and Effie Gray.

Massimo Stanzione (1585–1656), Seven Archangels: Acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art from Sabrier & Paunet.

EVENTS

This month we have picked out a selection of new and previously unhighlighted events from the UK and from further afield. For a more complete overview of ongoing exhibitions and talks, please visit our Calendar page.

UK

Wordlwide

DRAWING OF THE MONTH

Gode Krämer, former head of the Graphic Art Collection and the Picture Gallery of the Kunstsammlungen & Museen Augsburg, has kindly chosen our 23rd drawing of the month.

Johann Ulrich Mayr (1630–1704)

Portrait of a woman, c. 1670

Red chalk, black chalk, heightened with white, on blue paper, 300 × 212 mm, Kunstsammlungen & Museen Augsburg, Augsburg, Inv. No. G 4879-73

The Grafische Sammlung Augsburg owns two very unusual portraits of a young woman by Johann Ulrich Mayr. Both are of almost the same size, drawn on blue coloured paper in the same technique and clearly depict the same woman. In both drawings, the heads, which are tilted in different directions, are executed with great care and sensitive colouring, while the body and clothing are only hinted at. Both women have their eyes downcast, appearing almost closed. As one of the two sheets is somewhat less elaborate, we have decided in favour of the more mature counterpart presented here. Although the drawing appears finished, it is easy to recognise how Mayr constructed it. The preliminary drawing in black chalk, which defines the light garment and the bonnet on the hair in terms of material and space with very loose, ingeniously simple lines, is reinforced by red chalk in the outline of the face and also in the eyes, mouth and nose. Mayr then adds light and thicker hatching in black and red chalk, blurs them and creates fine, very natural-looking gradations and transitions with this and the heightening applied with white chalk.

Despite the unfinished lower part, it can be assumed that the sheet is a final drawing; on the other hand, there is the second version, which is just as beautifully coloured and only slightly less finished. It is therefore possible that both works were very careful sketches for a painting. This is also supported by the fact that the Graphische Sammlung in Stuttgart holds another related drawing, executed in the same technique - albeit smaller - showing the same woman in profile this time. The inscription at the bottom, which is certainly not by Mayr, also corresponds to those on both Augsburg sheets and probably points to a common origin. The woman in the painting Woman with a Basket of Fruit by Mayr in Frankfurt's Städel Museum looks similar enough to the one depicted in the drawings to identify her as the same person. This becomes particularly clear when looking at the Stuttgart depiction, which shows her in profile: the high arched forehead, the straight nose, the small, firm, round chin and the heavy eyelids match in the drawings and the painting.

Even the striking and enchanting pink colour of the cheeks in the Augsburg drawings can be found in the painting. Neither the drawings nor the painting are dated. Werner Sumowski emphasises the influence of the Swiss painter Joseph Werner (1637-1710), who stayed in Augsburg from 1667-82 and who had married Mayr's sister Susanna here, on the Frankfurt painting. Kaulbach also sees the same influence in his catalogue text for the Stuttgart drawing, so that a date of around 1670 seems reasonable for our drawing.

The drawing is in the exhibition Augsburger Geschmack ("The Augsburg Taste"): Baroque master drawings from the holdings of the art collections at the Kunstsammlungen & Museen Augsburg, Augsburg, through 28 Sep 2025.

DEMYSTIFYING DRAWINGS

On 27 June, the artists Nicholas C. Williams, Joana Galego, and Pippa Young joined Annette Wickham, former Curator of Works on Paper at the Royal Academy, for Timeless Materials – a panel discussion on drawing materials, techniques, and practice, held in partnership with The Drawing Foundation as part of the live events programme for the Trois Crayons exhibition Tracing Time.

Drawing has always been central to Williams’s work as a painter, and one month on, he revisits some of the questions raised by Wickham during the discussion and reflects on his own approach to drawing.

Could you describe the role of drawing in your current practice and how it has developed in this way? Which historical artists and drawing techniques have you gravitated towards in particular? And what have those interactions brought to your own work?

All my work, whether painting, sculpture or print, begins with a drawing. For paintings, I make initial sketches from imagination in small sketchbooks. The immediacy of drawing, particularly with charcoal, allows the transfer of images from thoughts to paper almost in real-time. Once I settle on a composition and the characteristics of the figures, I will ask people to pose who share those characteristics. Following the working methods of Caravaggio and his followers, I don’t make extensive preparatory drawings; instead, I refer back to the small sketches and draw from the model directly onto the canvas. Likewise, I sketch in other elements that I might need, such as still lifes, garments on lay figures, and so on, before underpainting.

I also regularly draw in response to seeing a particular subject or to hold onto a moment. And it is this aspect of drawing that I often gravitate towards when looking at the drawings of other artists – from Degas sketching a friend, Constable making a study of a tree, to Rubens drawing his young son. Such drawings represent flashes of intense observation that not only reflect a moment in their lives, but through the sense of familiarity resonate with our own.

How much did your training influence your approach to drawing and your interest in the art of the past? Are there historical techniques and graphic effects that you have found particularly resonate with your work?

As a child, I developed an interest in the work of the Old Masters through visits to the National Gallery, and so my training in drawing was invaluable. At sixteen, I joined college and was introduced to the principles of life drawing by a rather stern, but excellent elderly tutor, William Randall. The emphasis was on deep observation – seeking out volume through contour, knowing when to introduce weight to a line, and drawing on point. We had classes three to four times a week, working in silence with different models – one of whom, during every break, reminded the class he had posed for Augustus John, a statement that was unfortunately wasted on us.

When drawing from life, it is crucial to spend as much time looking as drawing. A wonderful example of the looking-to-drawing ratio is a sketch that Joana chose for our conversation – Rembrandt’s Two Women Teaching a Child to Walk. The subject demanded that Rembrandt observe and draw swiftly. As with all such sketches, determining the speed at which an artist worked is only an assumption, since we can never be certain how long they spent looking before making the next mark.

Perhaps the greatest lesson for me from studying Old Master drawings is their approach to rendering the figure. Generally, they worked from dark to light with descriptive passages of lines that follow form and reserved parallel shading for suggesting tone. It is a method shared with the painters of the Baroque, where the brushstrokes follow form – and there is no better example than examining the surface of a painting by Jusepe de Ribera.

Rembrandt, Two Women Teaching a Child to Walk, British Museum, London

Does it make a difference to you to look at original artworks where possible rather than from images?

While books are a vital resource, nothing competes with looking at the original for scale and touch. And there is also the mysterious charge that some drawings possess when you encounter them. After seeing original drawings by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele made on toned packing paper, I experimented with such papers – eventually sourcing a robust acid-free packing paper which I now use regularly.

Is the 'timelessness' of drawing and its materials significant for you?

When an artist draws, they are at their most vulnerable. Unlike painting, there is nowhere to hide, and a lapse in concentration will leave a trace. Lines reveal a hesitant or an assured hand, and the exposed nature of drawing means we are literally looking at the evidence of time preserved in every mark. And it is perhaps this element of drawing that makes Old Master drawings both elusive and compelling.

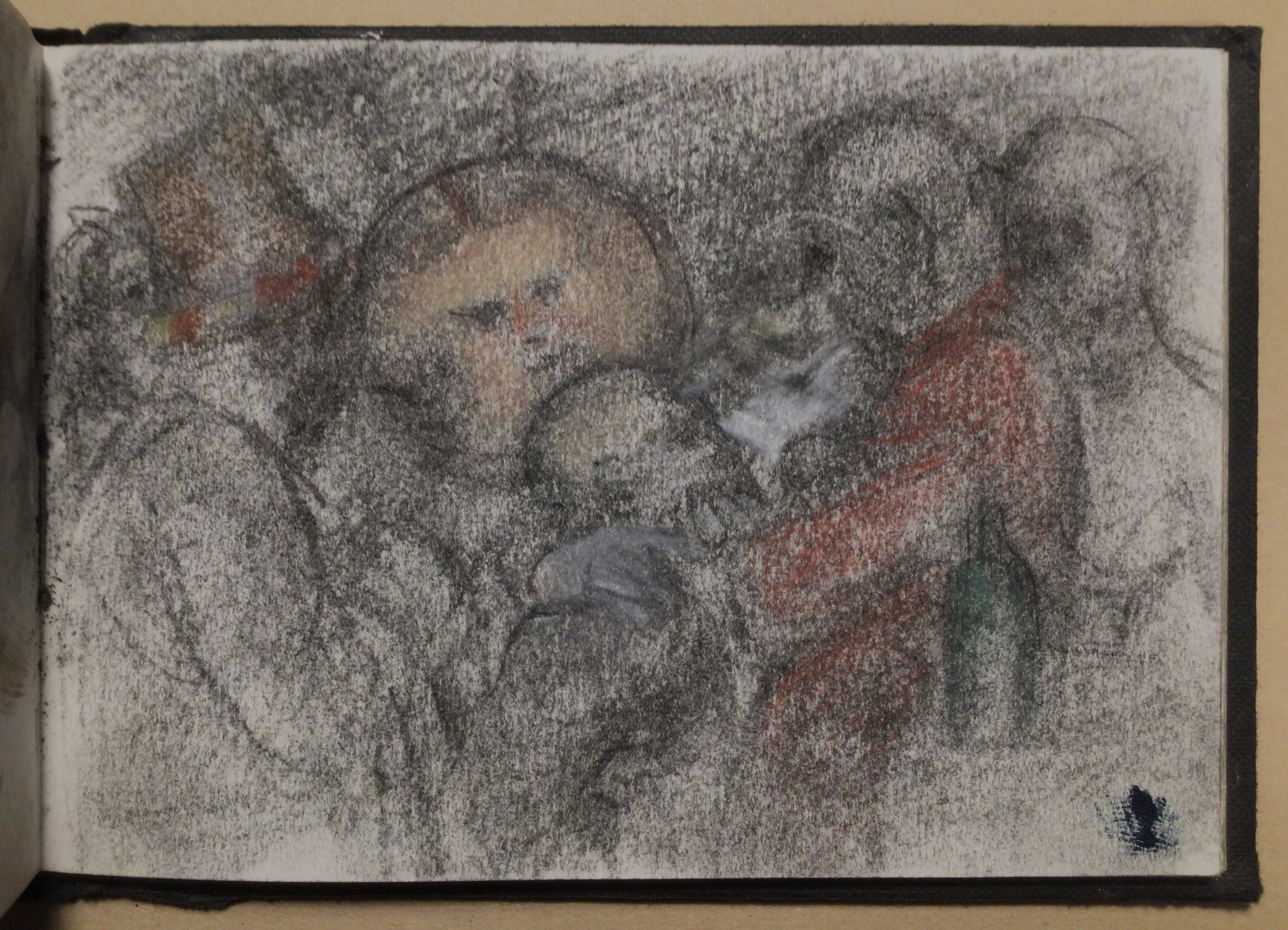

Nicholas C Williams, Sheet from pocket sketchbook: Initial sketch for a painting (2017), charcoal and pastel, 10.2 x 14.7 cm

How do you avoid pastiche when engaging with historical artworks? When is copying a good or useful thing, and when does it become problematic?

I have borrowed both overtly and subtly as a way into a work. However, there is always the danger, when borrowing components of an existing drawing or painting, of succumbing to pastiche. And appropriation is a slippery word – Pippa described it as sampling, which feels right. It is certainly a futile exercise to try and emulate the Old Masters; however, I am interested in employing their working methods to express thoughts and concerns about the here and now.

The works of the Old Masters are imbued with a sincerity of mark-making, driven by the purpose of a work. By contrast, I find it problematic when some contemporary works purport to be from life and yet are clearly copied from photographs – betrayed by affectation and fake pentimenti.

Are there any artists, past or present, who you think should be better known for their drawings?

To a wider public – Rubens and Annibale Carracci for their sheer intuitive brilliance; Watteau for the humanity that permeates almost every drawing that he made; Piazzetta for his understanding of reflected light and his ability to close in on the figure while conjuring whole scenes within a confined space; Käthe Kollwitz for her raw power; and Adolph Menzel for his tireless curiosity – the belief that every person or subject is worth drawing and for having eight pockets in his overcoat to carry his sketchbooks and drawing materials.

The event recording of Timeless Materials will be uploaded to the Trois Crayons website in the coming weeks.

Nicholas C Williams, Point (2018), oil on canvas, 107 x 138 cm

REVIEW

Victorian Treasures from Cecil French and Scott Thomas Buckle (24 May - 21 September 2025)

Leighton House, London

Reviewed by Nigel Ip

In 1986, the art historian Scott Thomas Buckle encountered the Cecil French Bequest on a visit to Leighton House. It presented a portion of the 52 paintings and drawings given to the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in 1953 and 1954, the majority by Edward Burne-Jones. Half of this collection has now returned to the historic house for the double bill exhibition Victorian Treasures, which includes a 21-piece showcase of Buckle’s own collection of Victorian drawings and watercolours, the subject of this review.

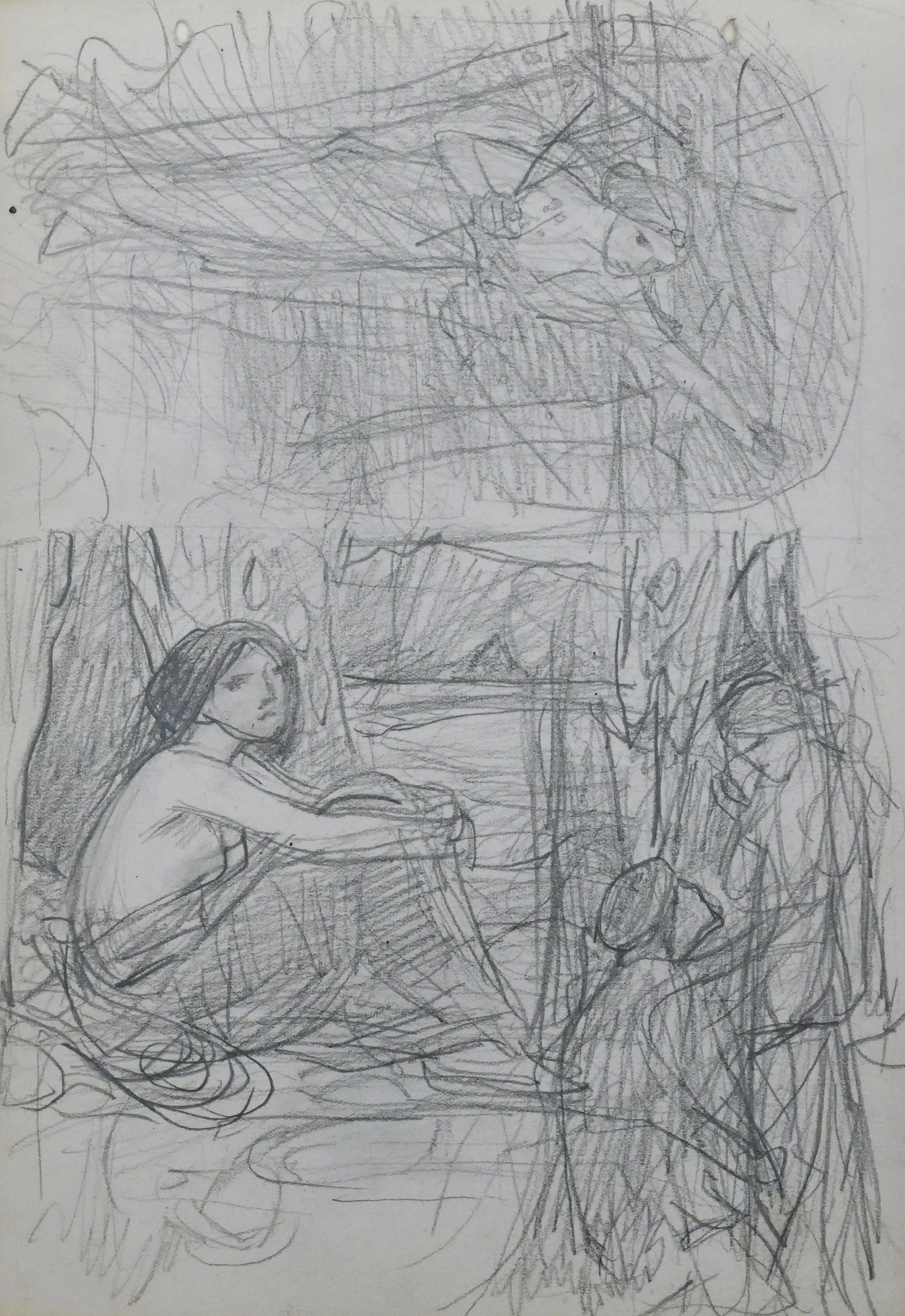

Connecting the two presentations are works by John William Waterhouse, whose Mariana in the South (c.1897) Buckle had seen in the 1986 display. Then inspired to build his own collection, he finally acquired a sheet of the artist’s sketches in 2006. Both are present in their respective galleries.

The selection from Buckle’s collection offers a good cross-section of different categories of Victorian drawing by major and lesser-known artists, male and female. Most of the sketches are for unrealised works, such as Frederick Richard Pickersgill’s sketch for The Industrial Arts in Time of Peace (c.1871) for one of the South Court lunettes in the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), a commission subsequently taken over by Frederic, Lord Leighton. Designs for illustration also join this category, for example, William Rimer’s unused frontispiece for Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (1860).

John William Waterhouse, Sketches for different compositions, including Phyllis and Demophoon. Scott Thomas Buckle Collection.

Some of the portraits are particularly arresting. Eliza Ramona Stillman’s snake-haired Sabina (c.1888) in pastels feels like looking into an oval mirror, petrifying those viewers who dare to match her enchanting Medusan gaze. There are portraits of well-known figures like the young Walter Crane, William Michael Rossetti, even a caricature of Simeon Solomon and Henry Holiday on the back of a letter. George Richmond’s vivid watercolour portrayal of an unknown lady, Portrait of a lady (1848), is arguably the best.

What makes this exhibition unique are the amusing insights into how certain drawings were acquired, particularly in an area that has remained relatively unfashionable to this day. Buckle's pragmatic, research-oriented approach has often enabled him to identify ‘sleepers’ and misattributions as a consequence of his ever-expanding knowledge of the Victorian period.

A good example is John Everett Millais’ After the Race (c.1841) - drawn at the age of 12 - which Buckle acquired from an eBay seller who believed it was by Judith Lear, Millais’ niece. Similarly, Fortitude - An Aristocrat on the Way to Execution (c.1900) by Frank Cadogan Cowper was originally attributed to his friend, Dion Clayton Calthrop, until Buckle recognised it was a study for the painting in Leeds Art Gallery.

To conclude, one of Buckle’s most remarkable collecting projects concerns Edward Matthew Ward’s A Night with the Wards (c.1847), which originally formed part of an album owned by his wife Henrietta Ward that contained drawings by the couple which were exchanged throughout the early years of their relationship. While the remnants of the album were sold off individually by a dealer between 2006 and 2014, Buckle has acquired over 90 of them, almost reuniting the album in its entirety.

Victorian Treasures from Scott Thomas Buckle at Leighton House ©RBKC. Image Jaron James

Real or Fake

The Real or Fake section returns next month.

Resources and Recommendations

to listen

The Specialist: A Ten-Year Vermeer Attribution Project, with Gregory Rubinstein

In The Specialist, a new podcast series from Sotheby’s, Greg Rubinstein, Head of Old Master and Early British Drawings, reflects on the decade-long effort to reestablish a once-doubted Vermeer as an authentic, autograph work.

TO watch

The BBC’s hit art dealing show is back for Series 13. Presenter and journalist Fiona Bruce joins art dealer Philip Mould for a new four-episode season looking at putative works by Winston Churchill, Auguste Renoir and others.

to read

The Artist in Nature by Anita V. Sganzerla

A suitably summery read from Anita V. Sganzerla focuses on four plein air drawings and the artist’s draw to nature. A call to all readers to get outdoors with a sketchbook this summer.